Article Directory

The Widening Gyre: Ithaca College's Confident Plan vs. Its Anxious Reality

An open conversation was held at Ithaca College on October 10th (Board of Trustees holds open conversation to answer campus community’s questions - The Ithacan). The Board of Trustees, fresh from three days of meetings, was there to recap its progress for the community. The attendance figure was, to be precise, approximately 25 people. In a community of thousands of students, faculty, and staff, this number isn't just a statistic; it's a signal. A signal of what, precisely, is the critical question. Is it apathy? Or is it a quiet consensus that the official narrative, however well-intentioned, operates on a completely different frequency from the day-to-day reality on campus?

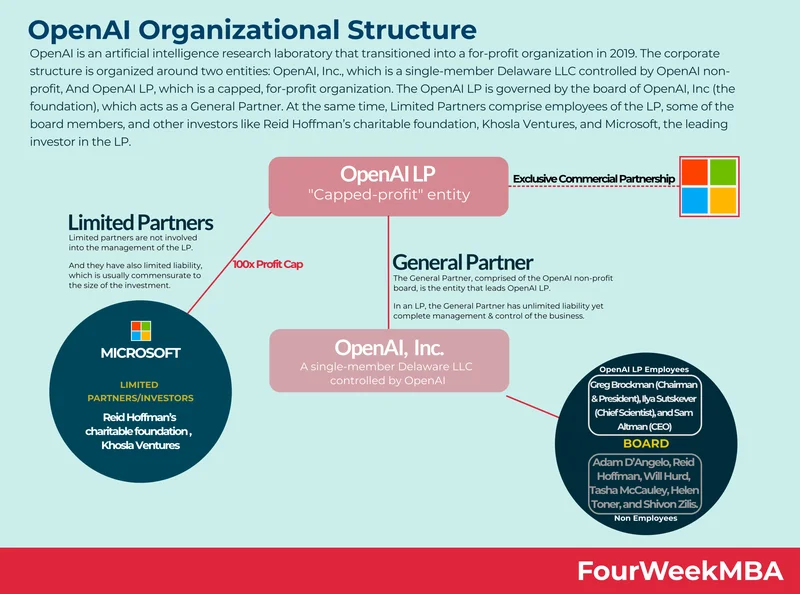

The board’s message, delivered by Chair John Neeson and Vice Chair Chris Palmieri, was one of methodical confidence. The primary objective of their fall meetings wasn't to chart a radical new course but to perform a systems check on the existing one: the multi-year plan to eliminate the college’s budget deficit by Fiscal Year 2028. They reviewed strategies for enrollment, philanthropy, and marketing. They discussed the ever-present specter of AI with the administration. They expressed comfort with the trajectory. Palmieri’s closing sentiment was unequivocal: "I want to see Ithaca Forever... I feel really confident that we’re going to hit all the targets."

Confidence is a valuable, even necessary, asset in any turnaround scenario. But it is also a sentiment, not a metric. And as the floor opened to that small crowd, the questions that emerged painted a starkly different emotional landscape—one defined not by confidence, but by a deep and abiding anxiety. The disconnect between the two is where the real story lies.

The Blueprint and the Rivets

The strategy laid out by the board is, from a purely structural standpoint, logical and familiar. When an institution faces a deficit, it has three primary levers to pull: decrease expenses, increase revenue, and optimize the core business model (in this case, student enrollment). To guide this process, Ithaca has brought in a suite of consultants—Huron Consulting Group, Hanover Research, EAB—the kind of names you see when an organization decides it’s time for a deep, data-driven overhaul. The board is focused on the long-term integrity of the institution, a process Neeson describes as "right sizing" the college's finances to create a stable platform for future investment.

This entire exercise is like an architect reviewing the master blueprint for a skyscraper. The lines are clean, the physics are sound, and the projections show a stable, profitable structure upon completion. The board sees the finished building and, based on the models, has high confidence in its viability. They talk about future capital investments in dorms and event spaces as new revenue streams, looking ahead to the floors that haven't been built yet.

But the questions from the faculty weren't about the blueprint. They were about the conditions on the 15th floor, right now. One professor asked how the board would respond to employees who have endured stagnant wages and dwindling resources. Another questioned the adequacy of the college's AI strategy, a concern not about a line item in a budget but about pedagogical relevance in a rapidly changing world. A third asked how the board planned to navigate the profound, almost existential, insecurity rippling through all of higher education. These are not questions you can answer with a spreadsheet. They are the human variable in the board's equation.

Neeson's response to the question on wages was telling. He stated the college must first focus on productivity and financial stabilization before it can shift to new investments. It’s the classic, and often necessary, argument: we have to patch the hull before we can upgrade the cabins. But this puts the board and the faculty on two different timelines. The board is operating on a three-year fiscal horizon. The faculty are operating on the timeline of a mortgage payment, a grocery bill, and the daily challenge of doing more with less. How long can that tension hold before something gives?

A Tale of Two Ledgers

I've analyzed dozens of corporate turnaround plans, and the language is almost always identical. Terms like "right sizing" and "stabilization" are sterile euphemisms for a period of austerity. The critical question is never if austerity is needed—the numbers often make that plain—but how its costs are distributed across the organization and what the second-order effects of those costs are. You can cut expenses to balance a budget, but at what point do those cuts begin to degrade the very product you're trying to sell?

The board’s confidence appears to be rooted in the models provided by their consultants and the strategic plans presented by the administration. But models are only as good as their assumptions. The most significant, and least quantifiable, assumption in any turnaround is the sustained performance and morale of the workforce. When faculty members ask about wages and resources, they aren't just asking for themselves; they are providing real-time, anecdotal data about the health of the core operation. Their questions are a leading indicator of potential execution risk.

This is the central discrepancy in the Ithaca College narrative. The board is managing a financial ledger, and by all accounts, they are doing so with a clear-eyed, conventional strategy. The faculty, however, are trying to balance a human ledger, one where burnout, financial strain, and uncertainty are significant liabilities. The two ledgers are not currently aligned. The board sees a path to a balanced budget. The faculty sees a long, hard road to get there, and they are asking who will bear the cost of the journey.

What does it mean when only 25 people show up for an "open conversation"? It could mean the other 99% are perfectly content. Or, more likely, it means they believe the conversation is happening in a language they don't speak, about a reality they don't recognize as their own. The board is confident they will hit their targets. But the most important target isn't just a number on a balance sheet in FY2028. It's ensuring that when they get there, the institution they've saved is one its most vital people still believe is worth saving.

The Real Deficit Isn't Financial

The core problem at Ithaca College isn't the budget gap; that's just a symptom. The real deficit is one of perspective. You have a board looking through a telescope from 30,000 feet, rightly focused on the long-term destination. You have a faculty looking through a microscope at the immediate, cellular level of the organization. Both views are valid. Both are true. But they are not integrated. Until the macro-level strategy can be translated into a micro-level reality that feels sustainable—not just survivable—for the people on the ground, the college is running a dangerous risk. They might just "right size" their way to a balanced budget and find they've lost the institution's soul in the process.